|

Jews in Lucena

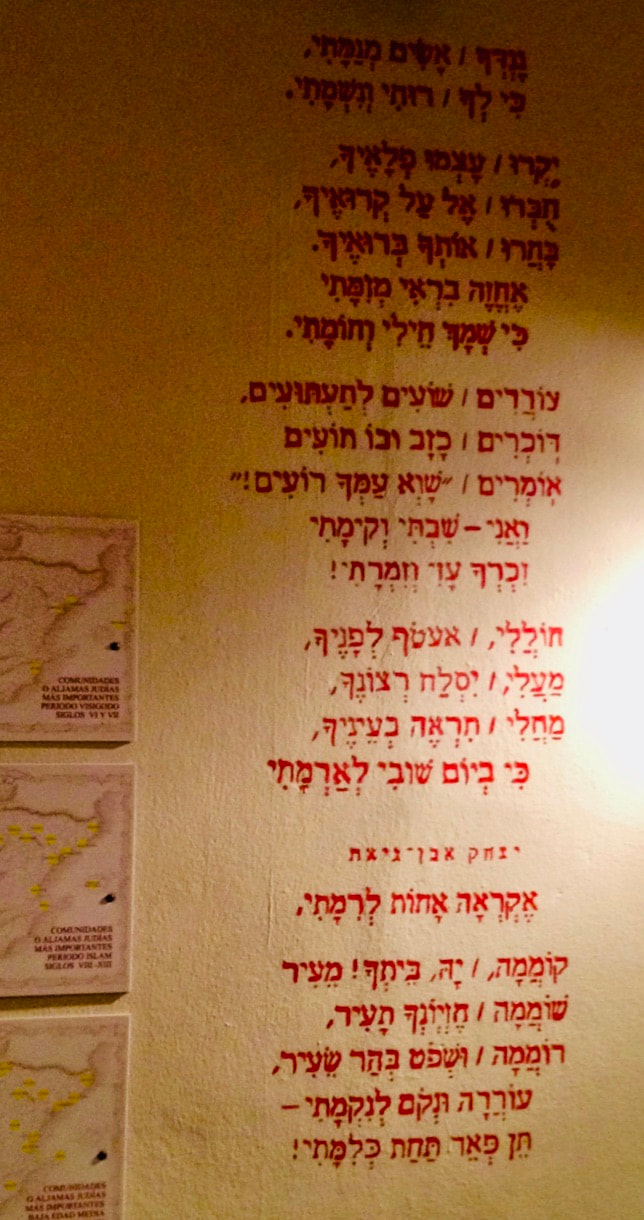

Regarded as the ”Jerusalem of Andalusia” and known as “The Pearl of Sepharad,” Lucena was the only town in Medieval Muslim Spain in which only Jews lived within the strong walls and wide moats. Eleventh-century Muslim geographer, Mohamed al-Edrisi visited Lucena, and recorded that the Jews of Lucena were richer than those of any other city. Lucena, 60 km southeast of Cordoba, was one of the most important centers of Jewish scholarship in Spain during the 11th and 12th centuries. Lucena’s rabbinical academy introduced a new curriculum that served as the model of Sephardic learning for generations. The entire community selected the Chief Rabbi, who was granted special privileges and acted as judge in the civil and criminal cases arising in the community. Rabbi Isaac ben Jehuda ibn Giat headed this esteemed Yeshiva. His successor was Isaac Alfasi, whose disciple was Joseph Ibn Migash, who taught Maimonides at that very same location. Today, Lucena is a small city with few traces of its Jewish past. Heinrich Graetz describes the Golden Age of Spain in Volume III of his classic History of the Jews. "The Andalusian Jews were equally active in Bible exegesis and grammar, in the study of the Talmud, in philosophy and in poetry. But the students in any one of these departments were not narrow specialists. Those who studied the Talmud were indifferent neither to Biblical lore nor to poetry, and if not poets themselves, they found pleasure in the rhythmic compositions of the new Hebrew poesy. The philosophers strove to become thoroughly versed in the Talmud, and in many instances rabbis were at the same time teachers of philosophy. Nor were science and art looked upon by the Spanish Jews as mere ornaments, but they exalted and ennobled their lives. Many of them were filled with that enthusiasm and ideality which does not allow the approach of any kind of meanness. The prominent men, who, either through their political position or their merits stood at the head of Jewish affairs in Spain, were for the most part noble characters imbued with the highest sentiments. They were as chivalrous as the Andalusian Arabs, and excelled them in magnanimity, a characteristic which they retained long after the Arabs had become degenerate. Like their neighbors, they had a keen appreciation of their own value, which showed itself in a long string of names, but this self-consciousness rested on a firm moral basis, they took great pride in their ancestry, and certain families, as those of Ibn-Ezra, Alfachar, Alnakvah, Ibn-Falyaj, Ibn-Giat, Benveniste, Ibn-Migash, Abulafia, and others formed the nobility. They did not use their birth as a means to obtain privileges, but saw therein an obligation to excel in knowledge and nobility, so as to be worthy of their ancestors. The height of culture which the nations of modern times are striving to attain, was reached by the Jews of Spain in their most flourishing period. Their religious life was elevated and idealized through this higher culture. They loved their religion with all the fervor of conviction and enthusiasm." Graetz, Heinrich, History of the Jews, Volume III, P 235, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1894 I visited Lucena in October 2013, where I met with the director of the town’s museum, Museo Arqueologico y Etnologico, which features a room devoted to the Jewish history of Lucena and prominently features a poem of R. Isaac ibn Giat on the wall of the Jewish exhibit. I also visited the parish church of Santiago just outside the medieval city walls, partially built with stones taken from the ancient synagogue of Lucena (see photo above), the Church of San Mateo built over the synagogue on the town square (see photo on home page), the former Jewish Quarter and the medieval Jewish cemetery (necropolis) beyond the town walls. http://www.redjuderias.org/google/google_maps_print/lucena-en.html http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/lucena

Rabbi Isaac ben Judah ibn Giat – His Life One of the earliest sources of information about our illustrious ancestor appears in The Book of Tradition (Sefer ha-Qabbalah) written by the Spanish Jewish historian and philosopher Abraham ibn Daud in 1160. "R. Isaac b. R. Judah b. Giat, one of the leaders of the city of Lucena, also displayed passion for secular knowledge and Torah from childhood. The two Nagids, R. Samuel and his son R. Joseph honored him and provided for him. When fate overtook R. Joseph the Nagid, the latter’s son Azriah fled to this R. Isaac. The Rabbi, remembering the kindnesses which Azariah’s elders had shown him, he in turn honored and provided for Azariah; indeed, he even wanted to set him up as the head of the community of Lucena and the other communities of Spain, despite the fact that Azariah was still but a lad. However, “except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it,” for R. Azariah [soon] passed away. So, R. Isaac b. R. Judah was appointed as rabbi [and served in that capacity] until 4849 [1089]. When he fell seriously ill, his slaves brought him to Cordoba for medical attention, but he soon passed away there on a Sabbath. Accordingly, his slaves removed his body from Cordoba, carried him all night and reached Lucena at dawn, where they buried him with his fathers. In addition to his secular learning and his knowledge of the Torah, he was also a great poet and learned in Greek wisdom. He spread the knowledge of the Torah and raised many disciples.” Cohen, Gerson D., A Critical Edition with A Translation and Notes, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1967, PP. 81-82. "The best known of his pupils were his son Judah ibn Ghayyat, Joseph ibn Sahl, and Moses ibn Ezra." Jewish Encyclopedia 1906. Vol 6, P:21. "He ... belonged to a rich and illustrious family of Lucena (not far from Cordova). Both the Ibn-Nagrelas gave him in his youth many proofs of their respect and he was devoted to them heart and soul. After the tragic end of Joseph Ibn-Nagrela, Ibn-Giat gave himself much trouble to raise Joseph's son, Abu Nassar Azaria, to the rank of rabbi of Lucena. But death deprived this noble house of its last scion. The community selected Isaac Ibn-Giat as its spiritual chief, on account of his learning and virtues. Liturgical poetry, philosophy, and the Talmud were the three domains sedulously cultivated by him." Graetz, History of the Jews, Volume III, P 284. When the Jewish leader R. Samuel the Nagid died in 1056, Rabbi Isaac wrote a long poem in Aramaic, which was recited publicly during the memorial service. Following the riots in Granada in1066 in which many Jews were slaughtered, the heads of surrounding communities proclaimed a fast day. Jews gathered in the synagogues to recite psalms and study the Mishnah. Rabbi Isaac composed an elegy, which was recited before a large gathering in Lucena. "In Cordova, Joseph ben Jacob Ibn-Sahal (born 1070, died 1124), a disciple of Ibn-Giat, was the rabbi.” Graetz, History of the Jews, Volume III, P 314. Moses Ibn Ezra, one of the greatest poets of the Spanish Golden Age, wrote about his teacher, Rabbi Isaac ibn Giat, “He was my teacher and from him I received instruction, so that the little water which I possess is a drop of his sea, and my slight knowledge a spark of his fire.” In Iyunim V’diyunim, Ibn Ezra considers Ibn Giat equal in stature to the two great poets who preceded him and influenced his work: R. Shmuel Halevi Ibn Nagrilah, the well-known civil leader of Granada (993-1056) and R. Shlomo Ibn Gabriol, the famous poet and philosopher (1021-1057). Rabbi Isaac Alfasi, a renowned Talmudic codifier, fled Fez at age 75 to Cordova, where most Jews received him with open arms. But not all. “Two other scholars, Isaac Avalia and Isaac ibn Ghayyat, envying his position, criticized his code severely. They attacked him for his independence in the treatment of the Talmud and for taking upon himself to enter final verdicts in legal questions.” Later in Lucena, Isaac Alfasi, "acted as the official rabbi of the congregation after the death of Isaac ibn Giat (1089), with whom he had some angry discussions." Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol 1, P:375: 1906. Rabbi Isaac is one of twelve names inscribed in the ancient Toledo Synagogue. His name also appears on the wall of the history of Jewish leaders at the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot, Tel Aviv. |

Rabbi Isaac ben Jehudah ibn Giat – His Works

"He was the author of a compendium of ritual laws concerning the festivals, published by Bamberger under the title of "Sha'are Simḥah" (Fürth, 1862; the laws concerning the Passover were republished by Zamber under the title "Hilkot Pesaḥim," Berlin, 1864); and a philosophical commentary on Ecclesiastes, known only through quotations in the works of later authors (Dukes, in "Orient, Lit." x. 667-668). The greatest activity of Ibn Ghayyat was in liturgical poetry; his hymns are found in the Maḥzor of Tripoli under the title of "Sifte Renanot." Bibliography:

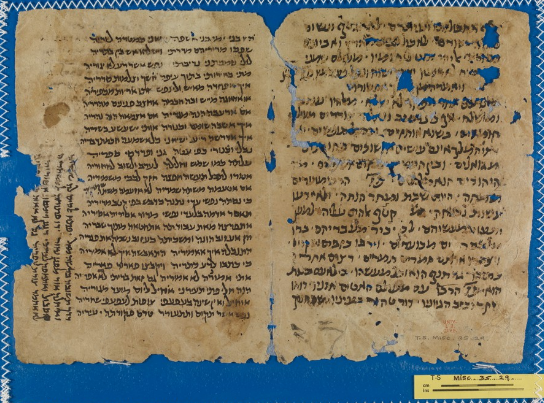

Fragment (above) of R. Isaac's Commentary on Ecclesiastes 8:13-15(T-S AS 21.284). Part of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection at the Cambridge University Library. It is interesting to note that one of the authors of the Jewish Encyclopedia article on Rabbi Isaac ibn Giat, was Cyrus Adler PH.D., President of the American Jewish Historical Society, President of the Board of Directors of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. Adler was also instrumental in securing the loan of the Judaica collection of Hadji Ephraim Benguiat for the Smithsonian Institution and authored the exhibition catalog in 1901, Descriptive Catalogue Of A Collection Of Objects Of Jewish Ceremonial Deopsited In The U. S. National Museum By Hadji Ephraim Benguiat. (This collection now resides in the Jewish Museum, NYC.) Also of interest, the De Sola listed in the Bibliography for the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia article is Abraham De Sola, a descendent of ibn Giat's daughter, Miriam (see below Miriam bat Isaac ibn Giat). De Sola co-authored Ancient Melodies of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews in 1848. “Rabbi Isaac Ben Jehudah Ben Giath, whom we have already named, is one of the most distinguished of the Hebrew poets in Spain. He gained repute also as a philosopher, physiologist, cosmographer, and astronomer, according the measure of light, which had been thrown upon these sciences at that period. As a poet he is admired for his striking and well-tuned sentences, and his exquisite taste in the use of language; but, on the other hand, his style is thought too highly finished, and too much laden with scientific ornament, which has caused it to be compared to the Alexandrian school of Greek poetry. His critics have, however, unanimously joined in praising his penitential hymns, found in the Liturgies of many synagogues for the services during the month that precedes the new year. … He composed also hymns for the Feast of the Passover and the great Day of Atonement, with a poetical paraphrase of the biblical narrative of Elijah’s prayers on Mount Carmel. The Isaac Ben Giath succeeded as poets Rabbi Joseph Ben Jacob Ibn Sahl, his disciple, who died A.D. 1124, at Cordova; and his own son and grandson, Rabbi Jehudah and Rabbi Solomon Ben Giath, both looked upon as masters of the art by such judges as Al Charisi and Judah Hallevi.” da Costa, Isaac, Noble Families Among Sephardic Jews, London: Oxford University Press, 1936. [Translated from Isaac da Costa, Israel en de Volken, 1850.] Rabbi Abraham, son of Maimonides, records in his essay Milchamoth that Rabbi Isaac ibn Giat had written a commentary to the Talmud. "Likewise, the great achievement of Maimonides in his Mishnah Torah is hardly conceivable without the preparatory work of his predecessors, the Rabbis Isaac ben Jacov Alfasi and Isaac ben Judah Ibn Gayyat. ... Gayyat has devoted himself to, and excelled in, three spheres of studies, Liturgical Poetry, Philosophy, and Talmud." Taubes, Rev. Dr. Chaim Zwi Ph.D,. Lekutay R. Isaac Ben Judah Ibn Gayyat to Tractate Brachoth, Delachaux & Niestle S.A., Neuchatel. Nacḥmanides quotes R. Isaac ibn Ghayyat on the custom of wearing black during Mourning "Torat ha-Adam," p. 27d, ed. Venice: 1595. Abraham Ben Nathan, French author born in the second half of the twelfth century published extracts from the halakic works of Isaac ibn Giat, Isaac Alfassi and Isaac ben Abba Mari in "Ha-Manhig" (The Guide), or as the author called it, "Manhig 'Olam," which he began in 1204 Jewish Encyclopedia: 1906. Vol 1, P:116. Polish scholar Bernhard Zombar, born at Lask in 1821, attended the universities of Würzburg and Berlin, and in 1871 he was appointed principal teacher of the Bet ha-Midrash of Berlin, a position which he held until his death. His works include: "Hilkot Pesaḥim," on Passover laws compiled by Isaac ibn Ghayyat, supplemented by a commentary of his own entitled "Debar Halakah" (Berlin, 1864). Jewish Encyclopedia:1906. Vol 12, P:694. Russian scholar Baer BenAlexander Goldberg published "Ḥofes Maṭmonim" (Berlin c.1846), "a selection of essays contained in old and rare manuscripts, these essays including: (1) 28 decisions of Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi); (2) letter of Sherira Gaon on the methodology of the Talmud, and the succession of the Amoraim and Geonim; (3) "Hai ben Meḳiẓ" Abraham ibn Ezra's psychology and eschatology, according to Ptolemy; (4) "Milleta de-Sofos," fables of the Geonim; (5) "Piyyuṭ Asher Ishshesh," a liturgic poem of ten strophes on the "Baruk she-Amar" of Isaac ibn Ghayyat." Jewish Encyclopedia 1906. Vol 6, P:21. References & Further Reading

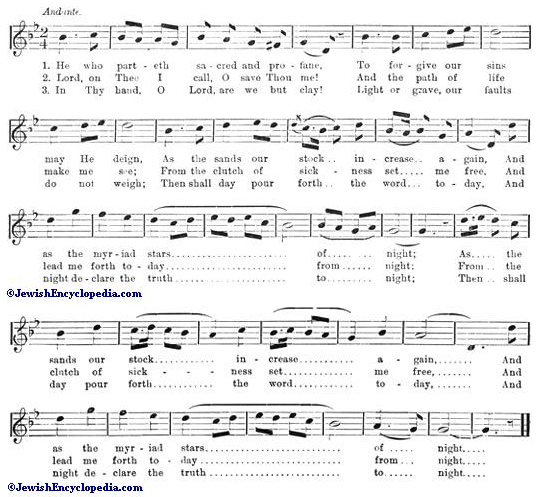

"Notable among his many Piyyuṭim, liturgical hymms, is Ha=Mabdil. "A hymn signed with the acrostic "Isaac ha-Ḳaṭon" (Isaac ben Judah ibn Ghayyat, 1030-89), obviously written for the Ne'ilah service of the Day of Atonement, but now used in the Havdalah at the close of the Sabbath. Of its many musical settings the finest is the following old Spanish melody (see below). Bibliography:

|